by Richard Hayes, FBIS

Assistant Editor

Odyssey – the Science Fiction, Space Art and Cultural Magazine of the British Interplanetary Society

Eric Frank Russell – Licensed Jester

“Look, if you ever take to the spaceways don’t worry too much about the ship – concentrate your worrying on the no-good bums who’ll share it with you!”

“There appears to be a deceitful law governing other worlds, to wit: that they look completely innocent while making ready to bite your nut off.” – from Men, Martians and Machines, Eric Frank Russell

An interest in science fiction featured strongly in the early years of the British Interplanetary Society. In Interplanetary, his history of the BIS, Bob Parkinson comments that “The ordinary members of the Society in those early days were practically one hundred percent Science Fiction readers. Arthur C. Clarke and Eric Frank Russell were to make names for themselves as Science Fiction writers, and Walter H. Gillings as a Science Fiction editor.”

Bob quotes Leslie Johnson, Secretary of the BIS in the early 1930s, saying that it was Russell who, along with Johnson, introduced the great author and philosopher Olaf Stapledon to the Society during a visit to Stapledon’s home in Cheshire, and “it appears that one of Eric Frank Russell’s greatest achievements was to unveil the world of science fiction and the BIS to Olaf Stapledon.”

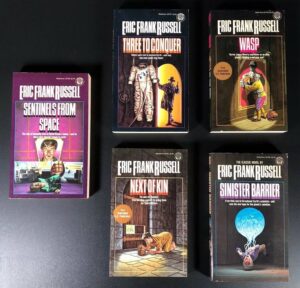

Even so, Russell was a ground-breaking author in his time. He was the first regular UK writer for the influential American magazine Astounding Science Fiction, and some of his stories had a noticeable impact on the development of science fiction. His 1939 novel Sinister Barrier explored the idea that humans are actually controlled by alien parasites that provoke and feed off our emotions, the stronger the better. So it was therefore not too surprising, then as now, that humanity has a staggering propensity to indulge in warfare and all the miseries that ensue, seemingly regardless of the consequences. He and Johnson wrote the 1937 short story Seeker of Tomorrow which pursued the theme of time travel into the far future in the spirit of HG Wells.

He also often considered scenarios where future space travellers encounter extraterrestrial cultures that pose profoundly difficult problems for human beings as they venture out into the cosmos. In his 1957 novel Wasp, which some regard as the best of his novels, a single human is pitted against an alien bureaucracy. In his characteristic light-hearted style, Russell describes a secret agent working undercover for Earth during an interstellar war with aliens from Sirius. Even though the forces of Earth are outnumbered, he causes havoc on the enemy’s planet by acting as a wasp – an insect which, as we all know, merely by threatening to sting can create mayhem by buzzing around inside a car being driven at speed. The driver might even be terrorised into crashing the vehicle.

Our hero works surreptitiously to spread anti-war propaganda, damage the enemy’s economy through using counterfeit currency, and tie up the military authorities in futile investigations. He moves on to killings and bombings, seeking out malcontents to use as scapegoats, all along aiming to spread alarm and despondency amongst the general population. Clearly, by any of our standards these days, he’s a terrorist. The reader is never actually told the cause of the war, or whether either side has the moral high ground, but tends to assume that Earth must be in the right because, well, that’s where we come from. There is an unavoidable question as to how far readers could condone violence against possibly innocent people just because they believe their cause to be just. It’s a message as relevant today – perhaps even more relevant – as it was when Russell was writing.

But it was his tales of interplanetary exploration that caught the imagination of those with an interest in space travel. A series of linked short stories during the 1940s, describing the adventures of a team of explorers roaming the Solar System and beyond, was collected in Men, Martians and Machines from 1955, and one can be struck by similarities to the planet-hopping exploits of later television series such as Star Trek.

Here is a multi-racial crew – the tentacled Martians have contempt for the awful smell of humans but a love for the game of chess, and are essential to the success of the mission – and robots can sometimes save the day. Together they face many of the now well-known potential crises of space travel, dealing with the consequences of a meteor strike on a spacecraft on a journey to Venus, and then plunging uncontrollably towards the Sun, followed by excursions to planets in other star systems where the inhabitants present unexpected problems.

One world is occupied by AI machines with a communal intelligence, whose programming makes it hard for them to cope with the abnormal, as humans and Martians definitely are, or anything which does not work according to their programmed rules, resulting in a scientific desire to dissect beings which display independence. It does make the reader wonder how AI might behave if, or when, it ever does develop true intelligence, though here on Earth it would, of course, be far more understanding of human behaviour, wouldn’t it? Let’s hope so.

On a forest world, they encounter a humanoid race that lives a symbiotic life with trees, sharing their existence and their faculties, and who don’t take kindly to humans and Martians intruding on their peaceful lifestyle. Perhaps there’s a message for any future ambassadors who might think they know better than the local inhabitants. Another planet features particularly unpleasant aliens who can deceive the human (and Martian) mind in remarkable and ingenious ways.

An outstanding feature of these stories, as in many of his others such as the 1952 short story Landing Party, and particularly his Hugo Award winning Allamagoosa of 1955, is that they are told with a degree of humour, so often targeting bureaucracy and officialdom, but also regarding the everyday events of life in space. In his history of science fiction Billion Year Spree, Brian Aldiss referred to Russell as the “licensed jester” to John W. Campbell as editor of Astounding magazine.

Our understanding of the universe and the technology of spaceflight has progressed immensely since the days when Russell was writing, but possibly the key message emerging from so much of his fiction is that, despite all the perils and trials of future space exploration, it might actually be fun. A review in the Oxford Mail at the time suggested that “Many writers have followed the trail Mr Russell blazed. Most of them lack his drive and wise-cracking humour.” Surely any enthusiasm, for any subject, needs to employ a smile to balance the seriousness.

As Russell expressed it so well in Men, Martians and Machines: “Space-conquerors, bah! Nutty, all of them, just like you and me!”.